There is a threshold, or maybe a small speed bump, that we must cross when we are about to change our identity or add another one to the deck of identities we already have. This threshold involves a “coming out” to others. We do it by calling ourselves this new name, awkwardly and gingerly at first, until it feels natural.

And this public proclamation to others, this voice we are giving to something that grew silently until now, is also a “coming out” to ourselves. We try it on for size, we play with it, we wonder why we haven’t done it earlier. Because we’ve already had this identity within us for a long time but were afraid to claim it.

Becoming an artist is exactly like this.

It may take someone seeing your work, something you call “dabbling” or “doodling” to avoid judgement, and telling you that they like it. Do you show it anywhere? Can I buy it? Can you make one for me?

Or it could be you getting a community center art class as a gift on your birthday and wanting more after it’s over. Or finding your high school drawings in a long-forgotten file and feeling a longing to make art again.

I remember my speed bump moment well.

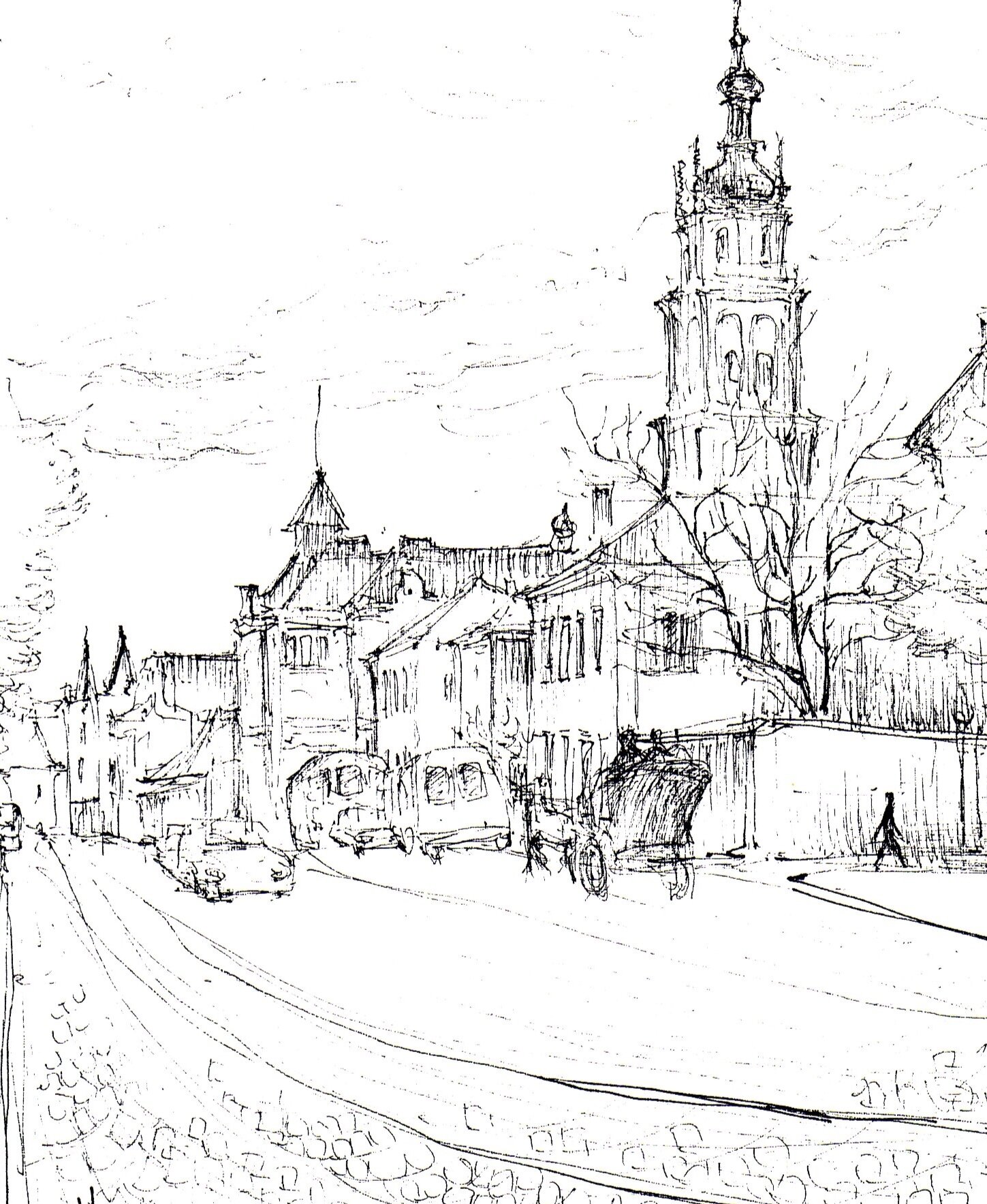

Sketch of a street in Lviv

I’ve always been making art in some form or another, and my parents recognized this interest early and enrolled me in all kinds of art workshops and schools since I was 8 or 9. This was my after-school activity of choice. I was also okay in choir, half-decent on piano, miserably bad on violin, D- in theater arts, and immediately bored with any kind of sports.

So, art it was. When the end of high school came around, it became clear to me that “artist” was not a career choice. Professional artists, so it was rumored, did exist, but I’ve never met one until, ironically, I was getting lessons in preparation for architecture school entrance exams. You could see their work in museums but they were like these mythical creatures that lived somewhere in their secret studios, hidden from the turmoil of daily life and separate from the rest of us.

I realize that this perception was probably uniquely Eastern European. Back in the U.S.S.R., artists were subsidized by the government and were free to create…as long as this creation promoted the message of the Communist Party. They didn’t need to make money. I guess they were a kind of an affiliate occupation to the politicians.

But, it’s high school, and my classmates are choosing majors and universities left right and center, and I am spending my summers on job sites with my tile contractor dad. What’s it going to be?

I accidentally stumble on a set of drawings for a store remodel at one of the job sites - and the gears in my brain suddenly align with a click. School is easy and I like drawing stuff. I can do this!

I’ve never met an architect before.

A first year fantasy art project

I go on to enter architecture school in Odessa and study there with mixed success for three years. Mixed, because I love exploring possibilities and hate getting half-baked projects done on time. I overthink.

And my favorite classes are studio art. I develop mad watercolor skills and get top marks. I’m also really good at math. And skipping classes I don’t like.

In my third year, my family moves to the U.S., and the clock re-sets. After settling in, I get back into school and take a community college watercolor class for fun. The teacher, himself an established studio artist, tells me that if architecture doesn’t work out, I could always be an artist.

I brush it off.

A portrait of a classmate from Odessa

Eventually, I do finish architecture school (by some miracle, because I have not learned to stop thinking and start doing by then). I graduate at the front end of the Great Recession and I can’t land a job in architecture. It’s not happening.

I take a retail job I am completely overqualified for and sign up for another watercolor class. Again, the teacher wonders out loud what exactly I am doing in this class. I should be teaching it.

But I do not yet call myself an artist. I “dabble” and “doodle”. It’s a form of stress relief, something I turn to in times of uncertainty when things aren’t going the way I planned them to. It’s an outlet for angst and depression.

Flamingo at the Sacramento Zoo

And one day, my then-husband comes home and tells me that someone at his work saw one of my drawings and became interested in my work. Oh huh. They want to see what else I got.

About the same time, I enter my first ever group show.

The co-worker buys one of my paintings and pays me to get it framed. The frame is more expensive than what I charge for the painting.

But now, I begin trying the artist identity on. I practice in my head: “I’m an artist.” I don’t come back to the retail job after having my first child, and I start a blog talking about my art process. I enter more and more shows and make more and more art. Finally, I call myself an artist.

The Paper Bags, the first painting I ever sold.

It takes a while to feel natural. The imposter syndrome loves creative people, thanks to the gap between what we know to be “good art” and what we produce. But eventually, with enough sales and validation from others, I claim the title for good.

I’m an artist.

It is now part of my identity, along with “mom”, “daughter”, “architect”, and soon, “wife.” I don’t give it a second thought or skip a beat when I say I’m an artist. And the truth is, I could have claimed that title long before I did. It was clear to everyone around me that I was an artist, but it took a while to convince the toughest audience - myself.

I will finish with another quote from Seth Godin:

“Are you an artist? Of course you are.

Artists make change happen. Artists are humans who do generous work that might not work. Artists aren’t limited to paint or museums.

You are an artist as soon as you announce you are.”